In a post I made a couple of months ago about policing and schools with majority-minority populations, one of the replies to my post reminded me of how there was a connection between what I talked about and something called the “school-to-prison pipeline.” And, it is indeed the case that there is a connection between the post I wrote about a couple of months ago and the school-to-prison pipeline.

But what it is the school-to-prison pipeline?

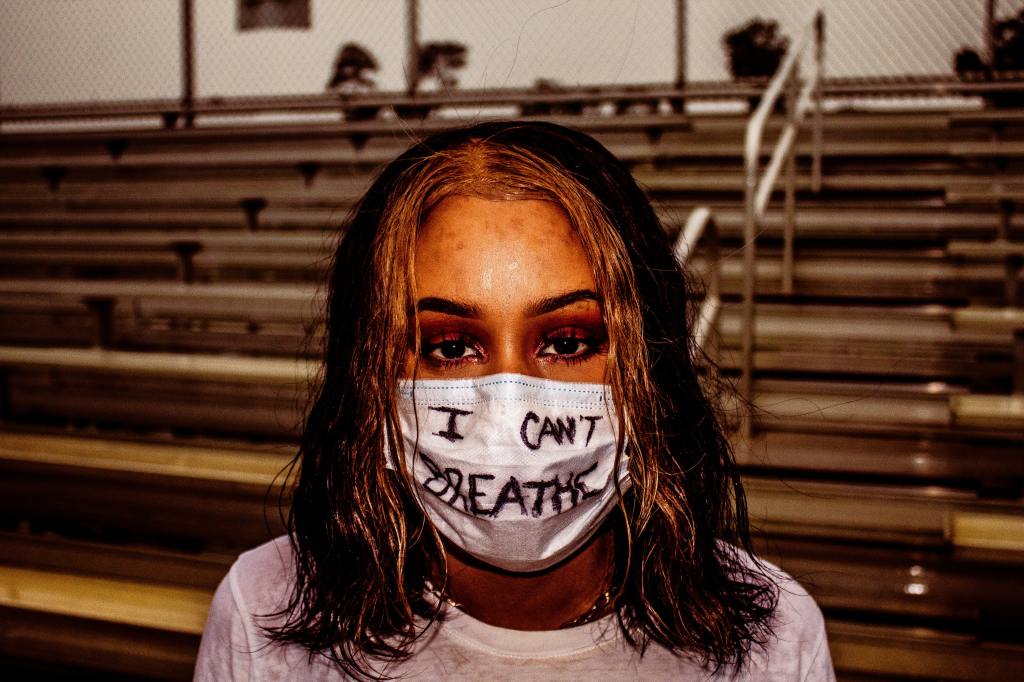

In short, it is “a disturbing national trend wherein children are funneled out of public schools and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems.”[1] This trend, which some kids from disadvantaged backgrounds are particularly vulnerable to (hence, this is an issue that often disproportionately affects kids of color and kids with mental health issues, to name two particular populations), involves isolating and punishing kids who cause trouble in school, in the process pushing them out of school and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems. In many such cases, various educational and counseling services might be most warranted, but instead students are often isolated and punished.

Some issues that lead to the school-to-prison pipeline include, but are not limited, to:

- Zero-tolerance policies, which impose severe punishments upon students regardless of circumstances. Such policies are often punitive to the point that the punishment does not fit the crime. Such policies can push students out of the “school” part of the school-to-prison pipeline.

- Police officers at schools, who are often responsible for policing the hallways at schools—a role usually reserved for teachers and school administrators. This can lead to something called school-based arrests—an issue that happens with some frequency.[2] Worse yet, these arrests can happen on quite a few occasions for minor behaviors,[3] issues that might not have resulted in arrest were it not for police officers at schools.

- A lack of resources for many schools, which means that the extra educational support or counseling support that a troubled student might need is not available. Because of that lack of availability to such vital services (and generally the lack of ability some schools have in providing vital services), students can be at an increased risk for dropping out and for future legal involvement.[4]

So how do we address this pipeline?

For one thing, I think we need to go back to a question I asked in my previous blog post on policing and schools with majority-minority populations: Should we really have police officers in schools? I know that “abolish the police” is a controversial idea, but if police in schools don’t protect the schools, don’t protect the students at the schools, and mostly serve as a major enabler in the school-to-prison pipeline, then I honestly think that law enforcement at schools is doing way more harm than good. One other thing I will add is that if there must be law enforcement in schools (and I’m not convinced personally that it is something we must have), I think it is a must that said law enforcement is competent in interacting with kids the age that they’re supposed to work with and protect.

For another thing, zero-tolerance policies need to be reevaluated. Not all actions should receive the same punishment. Creating an environment of restorative justice (repairing the harm caused by the crime, as well as giving the offender the opportunity to do better in the future) as opposed to punitive justice (punishing the offender severely, regardless of the severity of the crime) gives an opportunity for people to learn from their mistakes, not to mention that it creates an environment likely to decrease the chances of seeing the school-to-prison pipeline come to fruition.

Last, but not least, in cases where local municipalities are unable to provide the resources needed for schools to be well-resourced, I think that states and the federal government need to step in and make sure said schools and school districts are properly resourced. A significant piece of school funding relies on local property taxes,[5] which means that if you live in an area where property values are depressed, then revenue from property taxes is depressed. This creates a ripple effect which leads to school funding in a district also being depressed. Depressed school funding, in turn, results in a lack of access to many resources for the students who need them the most.

The school-to-prison pipeline is shameful. Hopefully, in my lifetime, progress can be made to address this problem.

[1] https://www.aclu.org/issues/juvenile-justice/school-prison-pipeline

[2] There were nearly 70,000 such arrests nationwide in the 2013-14 school year. I would like to see more current data, but this number gives us a sense of how much of a problem this was, as of a few years ago: https://www.edweek.org/which-students-are-arrested-most-in-school-u-s-data-by-school#/overview

[3] https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/metrocenter/ejroc/ending-student-criminalization-and-school-prison-pipeline

[4] https://www.aclu.org/issues/juvenile-justice/school-prison-pipeline

[5] https://www.npr.org/2016/04/18/474256366/why-americas-schools-have-a-money-problem